Penal military service (chongjun 充軍, also called junzui 軍罪, peili 配隸 or peijun 配軍) was one of the punishments in ancient Chinese law. It did not belong to the so-called "five punishments" (wuxing 五刑), yet it was a common penalty during the Ming 明 (1368-1644) and Qing 清 (1644-1911) periods. Delinquents were sent to military garrisons in the borderlands to work the garrison's fields (see military agro-colonies tuntian 屯田), to provide services to troops and officers, or to serve in the ranks of the army. Penal military service was a heavier punishment than exile (liu 流).

Earlier forms of penal military service were practised during the Qin 秦 (221-206 BCE) and Han 漢 (206 BCE-220 CE) periods. While the former applied this punishment (zheshu 謫戍, bingzu 兵卒) as a standard penalty, the Han used the penalty of sending delinquents to border garrisons (zuiren xubian 罪人戍邊, xibian 徙邊) as a commutation of the death penalty.

Between the 3rd and the 6th centuries, even women and underage males were punished with military service. Penal military service, following flogging (bianchi 鞭笞, 100 whips), shaving the hair, and tattooing, and likewise as a reduction of the sentence of capital punishment, was still in use during the Northern Dynasties 北朝 (386~581) and was found in the penal code of the Northern Qi 北齊 (550-577). Unlike exile, penal military service was not divided into grades discerning distances from the home prefecture. Emperor Wen 隋文帝 (r. 581-604) of the Sui dynasty 隋 (581-618) unified the two penalties of exile (liu) and penal servitude (tu 徒) into "assignment to defence" (peifang 配防) in the border regions. The Tang dynasty 唐 (618-907) combined the penalty of exile with penal service (jia yi liu 加役流).

The legal system of the Song dynasty 宋 (960-1279), which introduced the term chongjun, required that delinquents serving in the military be registered in the annexe of military household registers (fu mingji 傅[=附]軍籍). Another regulation stipulated that delinquents punished with penal servitude (tu) or exile (liu) were to be closely observed at the place of detention, and that the authorities punish them with penal military service along with tattooing (jue ci chongjun 決刺充軍) if they committed a further crime (see cipei 刺配).

The Ming dynasty distinguished between five grades of punishment by military service, namely "vicinity" (fujin 附近), "along the coast" (yanhai 沿海, both 1,000 li, c. 500 km; some authors interpret yanhai fujin as one single grade), in border garrisons (bianwei 邊衛, 2,000 li), distant borderland (bianyuan 邊遠, 3,000 li), far-away borderland (jibian 極邊), and garrisons in "miasmic regions" (yanzhang 煙瘴, both 4,000 li), meaning southwest China. There was a fixed number of garrisons where the penal service had to be performed. Initially, military service as a penalty was applied only to military officers, but later also to civilian delinquents. It could be applied to individuals, but also to whole families (see collective punishment, lianzuofa 連坐法). Normally, it was a reduction of the death penalty, and it was combined with 100 blows with the heavy stick (zhang 杖). The authorities discerned between lifelong service (zhongsheng 終身) and "eternal service" (yongyuan 永遠), in which a son or grandson took over the service after the delinquent's death.

This harsh penalty thus exceeded "normal" exile yet remained lighter than the death penalty. Penal military service was so common during the Ming period that the three grades of "normal" exile, with three grades of distance (sanliu 三流), were virtually replaced by the chongjun penalty. This tendency intensified the use of harsh penalties in the Ming legal system. The penal code Da-Ming lü 大明律 and the commentary collection Wenxing tiaoli 問刑條例 include many paragraphs on penal military service. It was also part of the jurisdictional regulations of individual government institutions and was often applied in individual cases by imperial edict. The Ming code itself comprised 46 paragraphs concerning penal military service. Emperor Taizu 明太祖 (r. 1368-1398) promulgated the code Chongjun tiaoli 充軍條例 with 22 paragraphs, and in 1550, a revised version with 213 paragraphs was issued.

The Ming code particularly applied prescribed penal military service for the incomplete forgery of seals by using seal-script characters, but not for the instrument of a seal (miaomo chongjun 描摸充軍, comp. Mingshi 明史 93, Xingfa zhi 刑法志 1). The Qing-period scholar Shen Jiaben 沈家本 (1840-1913) criticised penal military service as the most cruel punishment in the Ming legal system.

|

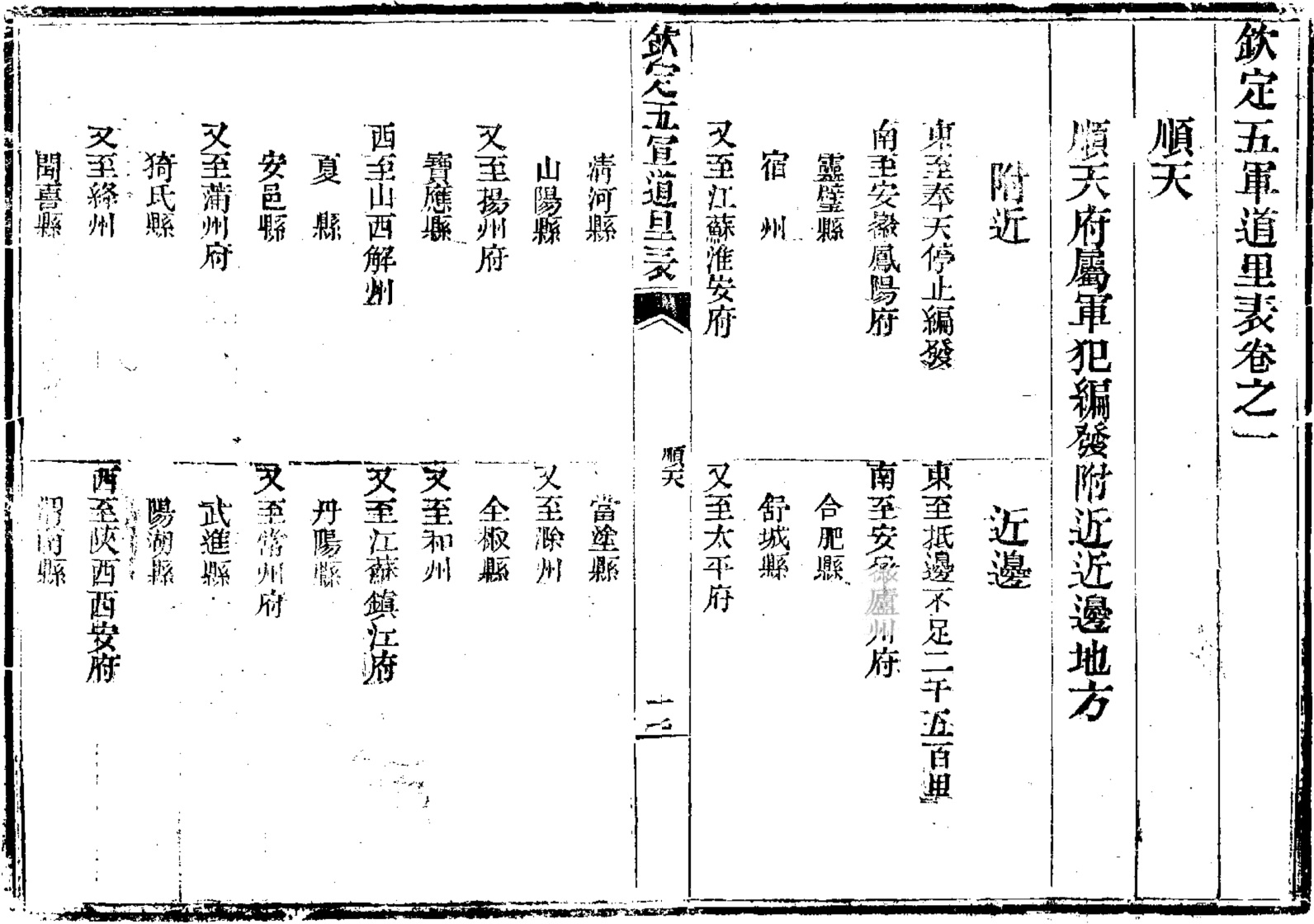

Beginning of the (Qinding) Wujun daoli biao 五軍道里表, regulating exile distance from Shuntian 順天 (Beijing), listing distances of the "vicinity" and of "close borderland". Revised 1809 edition. |

The Qing largely adopted the Ming system, but slightly adjusted the geographical ranges of penal military service. The "five [penalties of] military [service]" (wujun 五軍) were "vicinity" (fujin 附近, 2,000 li), close borderland (jinbian 近邊, 2,500 li), distant borderland (yuanbian 邊遠, 3,000 li), far-away borderland (jibian 極邊), and "miasmic regions" (yanzhang 煙瘴, both 4,000 li). All punishments began with ten blows with the heavy stick. The greatest distance of "normal" exile was 3,000 li, indicating that penal military service under the Qing was de facto an extension of exile and applied in cases of severe misdoings as a transgression of the normal exile (man liu 滿流). Delinquents, therefore, did not have to perform military service in the place of exile. The closest distance to the home prefecture was 2,000 li under the Qing, double that under the Ming.

On the other hand, the Qing did not apply collective punishment in this case. Moreover, the Qing legal system left open the possibility of amnesty (she 赦). The place of service was determined by the Ministry of War (bingbu 兵部) for delinquents from the capital, and by the respective provincial governor (xunfu 巡撫) for other cases. In 1772, a special code was promulgated for penal military service, Wujun daoli biao 五軍道里表 (based on earlier models such as Bangzheng jilüe 邦政紀略), which fixed the exact distances and procedures of exile for each crime. It became obsolete with the introduction of the new penal code Da-Qing xin xinglü 大清新刑律 in 1908. This code replaced penal military service with "normal" exile.