The Wusun 烏孫 were a nomad people living in the region of the Dzunghar Basin in the northwest of modern Xinjiang. They are mentioned in Chinese sources from the Han period 漢 (206 BCE-220 CE) until around 500 CE. It is not clear if the Wusun were an Indo-Iranian or a Türkic people. In his recent book, Beckwith reconstructs the original pronunciation of 烏孫 as Aśvin, and so seems to prefer the Indo-Iranian relationship.

The Chinese traveller and discoverer Zhang Qian 張騫 says that the Wusun originally inhabited the area of the Qilian Range 祁連山 and Dunhuang 敦煌, what is today the west of the province of Gansu. They were expelled from their homelands by the steppe federation of the Xiongnu 匈奴 and had to move farther to the west, just like the Tokharians (Chinese name Yuezhi 月氏) somewhat before. The Yuezhi killed the king of the Wusun, Nandoumi 難兜靡 (?-177? BCE), so that his heir had to seek refuge at the court of the Xiongnu khan. In several campaigns, the Yuezhi were forced by the Xiongnu to search for new land in the west, where they occupied the territory former inhabited by the Sakas 塞, in modern Uzbekistan. The Wusun then occupied the regions formerly inhabited by the Yuezhi.

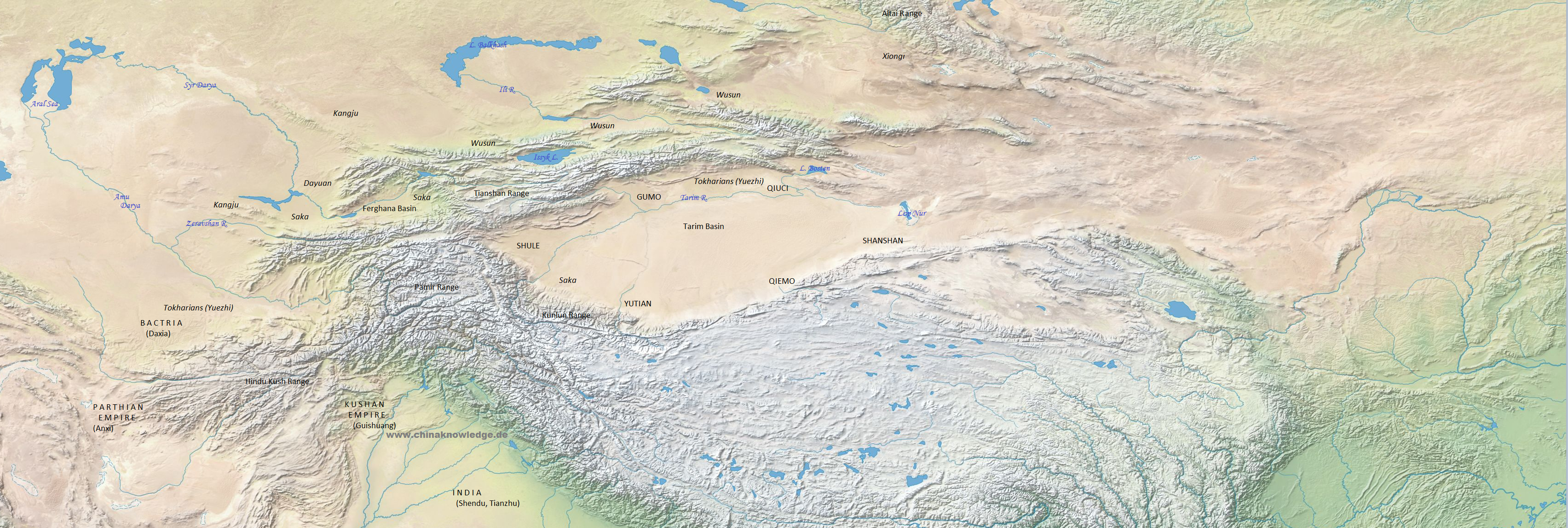

|

Based on Tan Qixiang 譚其驤, ed. (1995), Zhongguo lishi ditu ji 中國歷史地圖集, Vol. 2, Qin, Xihan, Donghan shiqi 秦西漢東漢時期 (Beijing: Zhongguo ditu chubanshe, 1996). Tribes and peoples in italics, states in normal letters. |

Emperor Wu 漢武帝 (r. 141-87 BCE) of the Han dynasty asked the khan (in the native language called kunmi 昆彌 or kunmo 昆莫) of the Wusun, Liejiaomi 獵驕靡 (177?-104?), to provide support against the Xiongnu and invited them to return to their former lands more east. In order to underline his will to cooperate, the khan of the Wusun was offered a Han princess as a wife. Zhang Qian was sent out to conclude this alliance, yet the Wusun refused to move the capital Chigu 赤谷 (either Narynkol, Xinjiang, or Dzhety Oghuz in Kazakhstan) to the east, but agreed to send a delegation to the court of the Han empire.

Only when Emperor Wu threatened to wage war, the khan accepted to conclude an alliance, sent tribute horses and welcomed the Chinese Princess Xijun 細君公主 as his wife. Princess Xijun wrote a famous poem (Beiqiuge 悲愁歌), in which she lamented her exile in the land of the barbarians. Because the khan was already an old man, he forced her to marry his councellor (?, cenzou 岑陬), to which Emperor Wu agreed. She bore a daughter but died soon so that the Han court had to send another wife to the Wusun, Princess Jieyou 解憂公主. Princess Jieyou lived for fifty years at the court of the Wusun and was first married to the cenzou, then to khan Wengguimi 翁歸靡 (93?-64/60?), the cousin and successor of Junxumi 軍須靡 (104?-93?). Princess Jieyou gave birth to five children, the oldest being the son Yuanguimi 元貴靡 (53-51). He had a half-brother called Wujiutu 烏就屠 (53-33), who had a Xiongnu mother. Princess Jieyou sent several letters to the Han court to provide support against the continuing raids of the Xiongnu.

Yet only in 72 BCE the Han court sent a support army of 160,000 men that heavily defeated the Xiongnu, massacred the population and killed their cattle. The Xiongnu soon took revenge and captured Wusun people and their beasts. The Wusun thereupon allied with the Dingling 丁零 and Wuhuan 烏桓 to punish the Xiongnu in 69 CE. At that occasion a Han army occupied Cheshi 車師, a state that had often sided with the Xiongnu in the past conflicts. The capture of this city enabled the Han empire to establish a direct contact with the land of the Wusun.

In 64 BCE another princess was sent to the Wusun, but before she had left the commandery of Dunhuang, khan Wengguimi died. Emperor Xuan 漢宣帝 (r. 74-49 BCE) decided that she may return because Princess Jieyou was married to the new khan, Nimi 尼靡 (64/60?-53), son of Junxumi. She bore him a son called Chimi 鴟靡. Prince Wujiutu killed Nimi, but fearing the revenge of the Han empire, he adopted the title of lesser khan (xiao kunmi 小昆彌), while he conceded that Yuanguimi bore the title of greater khan (da kunmi 大昆彌). The Han court accepted this method and bestowed both of them with an imperial seal. When both Yuanguimi and Chimi were dead, Princess Jieyou asked Emperor Xuan to be allowed to return to China. She died in 49 BCE. For the next decades, the institution of the greater and the lesser kunmi continued, and while the former was married to a Han princess, the latter used to be married to a Xiongnu princess.

The successors of the Greater Khan were Xingmi 星靡 (51-33), Zilimi 雌栗靡 (33-16), and Yizhimi 伊秩靡 (16-?), that of the Lesser Khan, -Fuli 拊離 (33-30), Anri 安日 (30-17), Mozhenjiang 末振將 (17-12/11), and Anlimi 安犁靡 (12/11 BCE-?).

At the beginning of the Later Han 後漢 (25-220 CE), the court was still reluctant to invest too much in the conquest of the Western Territories. Only in 74 CE the Wusun again sent tributes to the military commanders in Cheshi. In 80 CE general Ban Chao 班超 asked for support by the Wusun against the city state of Qiuci 龜茲. Emperor Zhang 漢章帝 (r. 75-88 CE) rewarded the khan of the Wusun with silks and resumed regular diplomatic exchange.

In the second century CE the Wusun lost more and more importance in the sphere of political matters. The newly emerging steppe federations of the Xianbei 鮮卑 and Rouran 柔然 drove the Wusun into the Pamir mountains. In 437 Dong Wan 董琬 from the Northern Wei empire 北魏 (386-534) visited the land of the Wusun. It is last mentioned in 938, when a chieftain of the Wusun sent tributes to the court of the Liao dynasty 遼 (907-1125).

Excavations on the site of the former land of the Wusun have shown that they were not simply nomads, but in many places also tilled the fields. Material findings in Wusun tombs can supplement data missing in historiographical sources.